Art After Chaos:

Art has always functioned as a method of storytelling, often used by high social classes to both educate and indoctrinate the masses. From religious and moral messages to political and propagandistic purposes, art when controlled by major institutions can be distant and at times unfeeling.

Many artists have strived to combat this narrative during the aftermath of WWI, creating groups and movements to combat what they saw as yet another failing on the part of society at large. Several of them had served in the war as soldiers, some even volunteering to fight for their countries. All those thoughts of patriotism and adventure were crushed under the might of what we now call the first modern war.

What had been sold to them as a just calling--an adventure even--would, in truth, become the most violent and widespread conflict of all time. With the rise in technology inevitably came new machines of war--tanks, machine guns, and poison gas to name a few--creating a new breed of conflict.

After a long period of what had been unimaginable suffering survivors were left in the wake of utter devastation in Europe. Citizens were enlisted or drafted as soldiers, staggering amounts of which would never return home. The men who did manage to find their way home came back to desolate places, broken and battered beyond recognition.

This chaos was reflected in the state of their bodies and minds, and artists who had suffered took to their craft to shed light on the horrors they'd witnessed. Determined to give honest perspectives on what had taken place both on the battlefield and at home they sought new mediums, new expressions.

George Gorsz:

One such artist was German-born George Grosz (1893-1959), who volunteered to become a soldier in 1914. He was discharged during his second enlistment for suffering a nervous breakdown in 1917 and was greatly against German militarism, later leading the Dada movement in Berlin before ultimately moving to the United States before the outbreak of WWII.

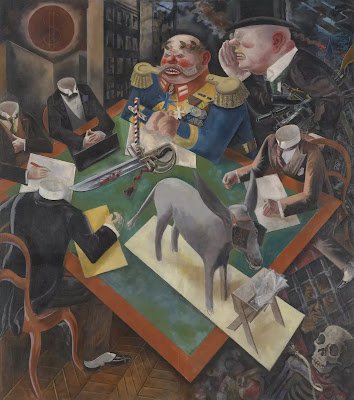

George Grosz, "Eclipse of the Sun", 1926, Berlin, Germany. Oil on canvas, 207.3cm x 182.6 cm (81.6 in x 71.9 in), Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY.

Paul von Hidenburg, president of Germany from 1925-1934, is the central figure wearing his military uniform as he leans over a table with several headless financiers seated around him. In the top left corner is an almost black sun, emblazoned with the dollar sign, and in the top right a man representing industry whispering in the president's ear, carrying several kinds of guns. The donkey in the middle is meant to represent the German people, who were blinded by their leaders, and at the bottom right is a youth trapped beneath a cage, a skull representing the death of the future sitting nearby.

Disillusioned with the way political powers had handled both the war and its effects, Grosz created this satirical piece. Hidenburg is painted almost beast-like, with a bloodied sword and cross positioned in front of him, signaling to the viewer both the cost of the war and the church's share of the guilt. The forms throughout are boxy and circular, and not at all true renderings of actual people. Grosz has made it clear to the observer that these are not people, but monsters.

Perspective in this piece is wild, with views from all angles setting the feeling of disease as we hover from on high, watching the corruption of the state happen before us.

Light has been painted to create feelings of unease, coupled with the blackened sun to show a dire state of being. The youth in the bottom right is a sickly yellow, further signaling the corrupted future for all German citizens.

The artist has used cartoonish characters to illustrate a glaring review of political leaders of his time, and in so doing broke several censorship laws, as many Dada artists were doing at the time. Comical though it may be, I wouldn't personally hang it in my house.

Otto Dix:

Otto Dix, "War Cripples", 1920, Dresden, Germany. Drypoint print, plate: 25.9 cm x 39.4 cm (10 3/8" x 15 1/2"); sheet: 32.5cm x 49.8 cm (12 3/4" x 19 9/16") Heinar Schilling, Dresdner Verlag, Dresden, Germany.

Otto Dix (1891-1969) was yet another artist who used wild caricatures and stark imagery to comment on both the war and the German government. Another volunteer for the war effort, Dix served until the end of 1918 and saw much time in the infamous trenches.

"War Cripples" is an honest perspective on the realities of soldiers returning home alive. Four men wander through the streets, all of them gravely disfigured, missing one or more limbs. The second-to-right figure has an almost ghostly face, likely signaling him as having "shell shock", a term coined before PTSD was understood. The one at the left and back of the procession appears almost robotic with his mechanical jaw.

The shoe store in the background is darkly humorous, the four men having little need for new shoes now.

This piece, again, makes use of wildly cartoonish characters who seem almost based entirely out of reality. The image is flat, bringing the central focus to the subjects in front who unabashedly march half-formed through the street. As an almost colorless print, there is a haunting, sick energy coming from it.

The artist's sharp hatching throughout the image creates an unsettling piece, as was his original intent. Lines move in all directions, making the piece both juvenile and frank. The print is based on a painting that was seized and destroyed by the Nazis once Hitler came to power, being viewed as debased and inflammatory.

This scene was a common one after the war, and Dix and his viewers would've been very familiar with the homeless, disabled, and mentally ill survivors that now littered the streets.

All of the promise of an easy war that would benefit the nation created feelings of deep bitterness, as can be seen in this piece.

As a modern viewer, I enjoy the comical morbidity of this piece, but it's impossible to be unsympathetic to the suffering on display here.

Käthe Kollwitz:

Käthe Kollwitz, "The Parents", 1921-22, published 1923, Dresden, Germany. One from a portfolio of 8 woodcuts. Composition (irreg.): 35.1 cm x 42.5 cm (13 13/16" x 16 3/4"); sheet (irreg.): 47.3 cm x 65.3 cm (18 5/8" x 25 11/16"). Emil Richter, Dresden, Germany.

The last piece I will speak on is my favorite, a beautiful woodcut print by Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). Another German citizen who had seen the horrors of the war--though this time not on the battlefield. Kollwitz is known for her deeply emotional pieces featuring the lives and turmoils of women, and this work is no different. Kollwitz lost her son Peter soon after the war started and was haunted by his death for the remainder of her life.

The two figures, presumably the parents of a lost soldier, huddle together on the floor, the taller figure holding a hand over his face and his other hand holding his wife close as they weep. They are placed centrally in the image, immediately capturing the viewer's attention

The raw emotion of this work cannot be understated. Kollwitz's choice to feature only two figures on an empty background leaves little room for anything other than the moment they share. With jagged etching, she draws the weight of both their clothes and grief, again the colorless print creating a sickly feeling. The man's hand is almost skeletal as he holds his own face, overcome with the loss of a child. The way Kollwitz depicts the mother as if she has lost all ability to move truly adds weight to the piece.

Her experience is clear, and the grief of losing her son is made plain to the viewer. Even without visible tears, we can almost hear them weeping, inconsolable as this world-shattering moment is shared. It would've been a common sight for all Germans, I imagine many of them becoming numb to the scene.

WWI was called the "Great War", not because it was good but because of the raw devastation wrought by it. Many artists used their own haunting experiences and new styles to not only express shared grief but also challenge the imperial and elite after such needless violence. Though many in Germany spoke out against the government, ultimately their children would carry the weight of the next battles. Everything culminated in the perfect storm, from Hitler's rise to power and the second World War and a continuation of the horrors seen before it.

Art tells stories, and often times they are hard pills to swallow or outcries against intolerance and corruption. But it can also be used to create the very narrative used to fuel both World Wars, and the many since these pieces were made. It speaks to us from generation to generation, but whether we listen or not becomes a choice that can shape the future.

Citations:

Hess, Heather. “Käthe Kollwitz. the Parents (Die Eltern) from War (Krieg). 1921 ... - Moma.” MoMa.Org, Museum of Modern Art, 2011, www.moma.org/collection/works/69684.

Hess, Heather. “Moma | the Collection | George Grosz. Republican Automatons ...” MoMa.Org, Museum of Modern Art, 2011, www.moma.org/s/ge/collection_ge/artist/artist_id-2374_role-1_sov_page-149.html.

Hess, Heather. “Otto Dix. War Cripples (Kriegskrüppel). 1920 | Moma.” MoMa.Org, Museum of Modern Art, 2011, www.moma.org/collection/works/69799.

Jess. “Collection Spotlight: George Grosz and ‘Eclipse of the Sun.’” The Heckscher Museum of Art, The Heckscher Museum of Art, 9 Aug. 2022, www.heckscher.org/5048-2/.

“The Roads to World War I: Crash Course European History #32.” Performance by John Green, YouTube, YouTube, 16 Jan. 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGlmlSTn-eM. Accessed 6 Nov. 2023.

Shawn Roggenkamp, "Käthe Kollwitz, In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht," in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed November 7, 2023, https://smarthistory.org/kathe-kollwitz-in-memoriam-karl-liebknecht/.

V, Audrey. “At Tate Britain, the Aftermath of Art after World War I.” Widewalls, Widewalls, 14 June 2018, www.widewalls.ch/magazine/world-war-one-art-tate-britain.

Comments

Post a Comment